+ + + + + + + + + + + + + + +

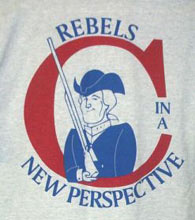

Earlier version of the Columbine High School rebel mascot on a t-shirt before April 20th 1999 (left) and today (right). Note the conspicuous absence of a gun in the modern image. Interestingly, Eric Harris chose to go by the nickname "REB" or "Rebel" while attending Columbine.

NEW YORK, Oct. 26 /PRNewswire/ -- It's been almost five years since Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold killed 12 students, a teacher and themselves in what remains the deadliest school shooting in U.S. history. Today's kids claim that most of the time no one at Columbine even thinks about "Columbine." They say they're just like high-schoolers everywhere. But more than 60 interviews with students and members of the community reveal a school that dwells simultaneously in its past and its present, reports General Editor Susannah Meadows in the November 3 issue of Newsweek (on newsstands Monday, October 27).

Last week Klebold and Harris showed up again. On Wednesday police released a 15-minute home video showing the boys taking target practice in the woods six weeks before they opened fire at Columbine. Tom Mauser, who lost his 15-year-old son, Daniel, says, "It's just too bad that it comes out in bits and painful pieces like this, rather than all at once." But the video was only the latest reminder. In the wake of last year's Oscar-winning documentary "Bowling for Columbine," a new film, "Elephant," depicts a massacre just like Columbine's in unrelenting detail.

"People keep saying, 'Well, now are you back to normal?' But there's never going to be normality here," says principal Frank DeAngelis. Since the shooting-era students left a year and a half ago, the school's taken its greatest steps toward recovery. Though tourists still peek in while school's in session, there's more giggling in the halls now. "For the three years after the tragedy, it was a very different place. It was too quiet," says counselor Susan Peters.

One indication that the school is reaching a new normal is that bullying is back. A student was recently suspended for writing a note to a friend about wanting to get rid of Jeremy Lodwig, the lone boy on the color guard. Why would someone write that? "I'm different," says the 15-year-old sophomore with bright orange hair glued into little spikes. "I have more girlfriends than I do guys." Heidi Cortez, who was a sophomore when everyone hiding under the library tables around her was killed, says, "Did we not learn anything?"

Because many kids -- and armchair psychiatrists -- think peer abuse may have contributed to Klebold and Harris's rage, some students are strangely sensitive for teenagers. "You want to be like, 'Oh, my God, I can't believe she does her hair that way, she's such a loser!' [But] you try and hold yourself back. You never know if you're going to be the one person to break them," says freshman Jaimie Hebditch, a "watergirl" for the JV football team.

Students whose older siblings survived the massacre are the most vigilant. Ty Werges, a sophomore on the soccer team, tells how he came upon some kids slamming shut the locker of a student who's mentally impaired. "I was like, 'Why are you doing that? Do you feel cool now?' They were shocked because out of nowhere someone sticking up for another kid is kind of weird," says Werges.

But the bullying stopped. Columbine's counselors (four out of five of whom spoke to Newsweek) argue that the massacre wasn't caused by bullying and that kids will always beat up on other kids. For them the return of such behavior is actually something of a relief. "Oh, it's a girl fight. Something normal," counselor Ken Holden says he hears colleagues say.

The real legacy of the massacre lies in what's missing. The Columbine mascot, a 1776 Revolutionary "Rebel" soldier, no longer carries a gun. The bare vinyl floors of the school are striking to anyone who remembers that all the carpet was ripped out after the mess of that day. The library, which was above the cafeteria and where most of the shootings occurred, has been removed and rebuilt in a different part of the school; now students eat their lunch in a sun-filled atrium that fills the space where the library used to be. The names of those who were lost are now inscribed on the memorial in the new library.

What's most surprising about Columbine is that, despite the ghosts of the past, all kinds of students -- flag-twirlers, cheerleaders, self-described dorks, drummers, soccer players, choral singers -- say they love coming to school here. "We take such a pride in our school," says Danny Beyer, a senior in the choir whose older sister, Lauren, survived 4/20. "Even though we might not be the best, but because this is our school."

Originally printed in Newsweek magazine